A team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg, the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt in Braunschweig and the University of Aarhus in Denmark demonstrated for the first time Coulomb crystallization of highly-charged ions (HCIs). Inside a cryogenic radiofrequency ion trap the HCIs are cooled down to sub-Kelvin temperatures by interaction with laser-cooled singly charged Beryllium ions. The new method opens the field of laser spectroscopy of HCIs providing the basis for novel atomic clocks and high-precision tests of the variability of natural constants. [Science, March 13 2015]

Atoms can lose many of their electrons at very high temperatures, forming highly-charged ions (HCIs). Such HCIs constitute a large class of atomic systems offering various new possibilities for high precision studies in metrology, astrophysics, and even for the search for new physics beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. Over the last few decades, laser spectroscopy of cold atoms or low-charge state ions has developed into today’s most powerful method for high-precision measurements. However, this was so far restricted to a few atomic and ionic species, and the preparation of cold HCIs constituted a major challenge in atomic physics up to now. The main obstacle arises from the usual production methods for HCIs, which require high temperatures of millions of degrees. But in order to exploit the power of laser spectroscopy, temperatures of less than one degree above absolute zero have to be reached; i.e. the thermal energy of the ions has to be reduced by a factor of at least 10 million.

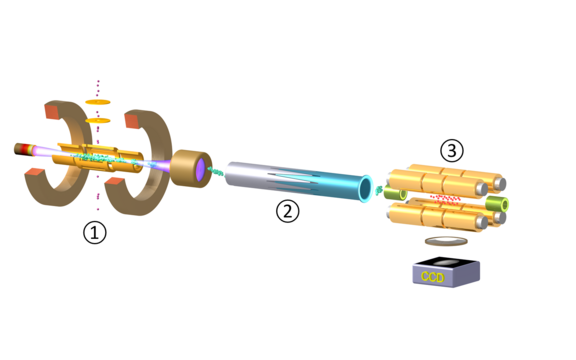

In a joint project by the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics Heidelberg (MPIK), the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) in Braunschweig and Aarhus University, a team of physicists succeeded in cooling HCIs down to sub-Kelvin temperatures and freezing their motion in vacuum forming a so-called Coulomb crystal. The procedure was demonstrated for the first time at MPIK in the group under José Crespo López-Urrutia. It involves three steps (Fig. 1), explains PhD student Lisa Schmöger, who built the deceleration set-up and carried out the reported experiment: First, HCIs are generated in Hyper-EBIT, an ion source which produces and confines ions at a million degrees temperature inside a dense and energetic electron beam in an extreme vacuum. Bunches of HCIs are then extracted from this trap, transferred through a vacuum beamline, slowed down and pre-cooled with a pulsed linear deceleration potential. The ions are very delicately transported into, and eventually confined in, CryPTEx, a cryogenic radiofrequency Paul trap developed at the MPIK in collaboration with Michael Drewsen’s group in Aarhus. Inside this trap, the HCIs bounce back and forth between mirror electrodes, slowly losing speed before they become embedded in a laser-cooled ensemble of light ions (singly-charged beryllium) which provide a cooling bath for the HCIs (providing so-called indirect or sympathetic cooling).

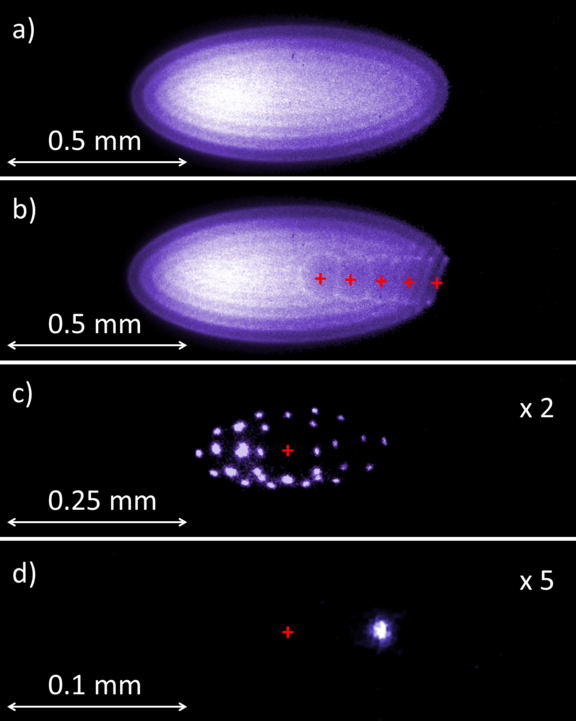

In a radiofrequency trap, the confined, mutually repelling ions are forced to share a small volume in space by a combination of electrostatic and oscillating electric fields inside a vacuum chamber. Additionally, the millimeter-sized beryllium ion cloud is cooled by a special laser such that the ions freeze out and form a Coulomb crystal once their thermal motion becomes negligible compared with their electric repulsion. Sophisticated laser systems built at the PTB by Oscar Versolato and colleagues are used at MPIK for this purpose. Once sufficiently cold inside the laser cooled ion ensemble, the HCIs crystallize as well, and can be stored in various configurations. The image displayed in Fig. 2a shows the pure beryllium crystal consisting of about 1500 ions imaged by a CCD camera which detects the fluorescence light emitted by each individual ion due to the laser cooling. In Fig. 2b five trapped Ar13+ionsappear as a chain of dark “holes” since they do not shine themselves, but repel the surrounding beryllium ions. Fig. 2c depicts a crystal of 29 beryllium ions with a single Ar13+ ion in the centre. The extreme case of only two remaining ions (one of each species) is demonstrated in Fig. 2d (with the invisible Ar13+ ion in the centre). Such ion pairs form the basis for quantum clocks and quantum logic spectroscopy, a technique developed by Piet Schmidt, the PTB group leader during his stay at Nobel laureate Dave Wineland’s laboratory at NIST (Boulder, USA). Here, the “spectroscopy ion” provides a high-precision optical transition used to keep the pace of the clock at 17 decimal digits accuracy. It is quantum mechanically linked to the “logic ion” which serves both for the cooling and readout of the spectroscopy ion: laser pulses enable the fluorescing logic ion to feel the quantum state of its nearly undetectable neighbour and changes strongly its own fluorescence yield according to the excitation of the other. José Crespo López-Urrutia explains with an analogy: “In this quantum married couple, the ions feel everything together, but whilst one of the partners cannot talk at all, the other one talks a lot. You then simply ask the talkative one.”

The efficient cooling of trapped HCIs opens up new fields in laser spectroscopy: precision tests of quantum electrodynamics, measurement of nuclear properties, and laboratory astrophysics. HCIs are rather insensitive to thermal radiation shifts and other systematic effects that could make a clock imprecise, and thus promise future applications for novel optical clocks using quantum logic spectroscopy. The ultimate goal of the MPIK-PTB collaboration will be to test the time dependence of natural constants such as the fine structure constant α, which determines the strength of electromagnetic interaction. For laser spectroscopy, theory predicts that the most sensitive atomic species with respect to α variation is 17-times ionized iridium. In preparation for these future studies, a new highly stable laser system will be installed by the PTB at MPIK to demonstrate the technique with the better known Ar13+ first. And the young scientists seem very eager to start playing with this tool and their novel cooling method.

(BF/ES)

Videoclip: Production of highly charged ions in an EBIT

Animation of the production process of highly charged ions in an electron beam ion trap (EBIT). Highly charged ions (for example Ar13+) are produced by successive electron impact ionization of injected neutral atoms and extracted from the EBIT in order to inject them into a cryogenic linear Paul trap.

Video: MPI for Nuclear Physics

Videoclip: Cooling process in the CryPTEx trap

The cryogenic Paul trap experiment (CryPTEx, you can see the gold-plated electrodes of the linear Paul trap). First, singly ionized Be+ ions are loaded into the Paul trap by photoionization of the incoming beam of neutral Be atoms. Subsequently, the cloud of trapped Be+ ions is laser-cooled until it undergoes a transition to the crystalline state. Last, highly charged ions coming from the EBIT are injected into the Be+ Coulomb crystal and become co-crystallized.

Video: MPI for Nuclear Physics

Videoclip: HCI in the CryPTEx trap (CCD images)

CCD-images of the successive loading of highly charged ions (Ar13+) into a laser-cooled Be+ Coulomb crystal. The Ar13+ionsdo not scatter light from the cooling laser and thus form dark structures of spherical shape along the central line of the bright fluorescing Be+ ion crystal.

Video: MPI for Nuclear Physics

____________________________________________________________

Original publication:

Coulomb crystallization of highly charged ions

L. Schmöger, O. O. Versolato, M. Schwarz, M. Kohnen, A. Windberger, B. Piest, S. Feuchtenbeiner, J. Pedregosa-Gutierrez, T. Leopold, P. Micke, A. K. Hansen, T. M. Baumann, M. Drewsen, J. Ullrich, P. O. Schmidt und J. R. Crespo López-Urrutia

Science 347 (6227): 1233-1236; DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa2960

EBIT group, MPIK (José Crespo López-Urrutia)

Quantum Logic Spectroscopy group, PTB (Piet O. Schmidt)

Ion trap group, U Aarhus (Michael Drewsen)

Eine Bremse für kreiselnde Moleküle (MPG press information 13 March 2014)

Photon recoil provides new insight into matter (PTB press information 30 January 2014)

____________________________________________________________

Contact:

Lisa Schmöger

MPI for Nuclear Physics

Phone: +49 6221 516-331

e-mail: lisa.schmoeger@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Dr. José R. Crespo-López Urrutia

MPI for Nuclear Physics

Phone: +49 6221 516-521

e-mail: jose.crespo@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Prof. Dr. Piet O. Schmidt

QUEST Institute for Experimental Quantum Metrology

Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt

Phone: +49 531 592 4700

e-mail: piet.schmidt@ptb.de

Prof. Dr. Michael Drewsen

The Ion Trap Group

QUANTOP - Danish National Research Foundation's Center for Quantum Optics

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University

Phone: +45 8715 5679

e-mail: drewsen@phys.au.dk