“Our whole universe was in a hot dense state. Then nearly fourteen billion years ago expansion started. Wait ...” – thus begins the title song of the US comedy series “The Big Bang Theory” which aired the first time in 2007 like a big bang and expanded to about 14 million viewers in the USA since. The series is about two brilliant physicists, Dr. Leonard Hofstadter and his roommate Dr. Dr. Sheldon Cooper,whose combined IQ of 360 is accompanied with social deficits. Together with their colleagues, an astronomer and an engineer, they personify a geeky microcosm which regularly collides with the real world. The latter is represented in the first place by the pretty neighbour Penny, a waitress who lives next door to the geeks.

The sitcom was created by Chuck Lorre and Bill Prady – with an eye for detail when bringing the world of nerds and geeks on the screen. They also put emphasis on authentic science: whiteboards show 'real' formulas related to the research work of the protagonists, a banana gets flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then shattered by a hammer to put it in muesli and even a real-life Nobel laureate (George Smoot) has a guest appearance in the show.

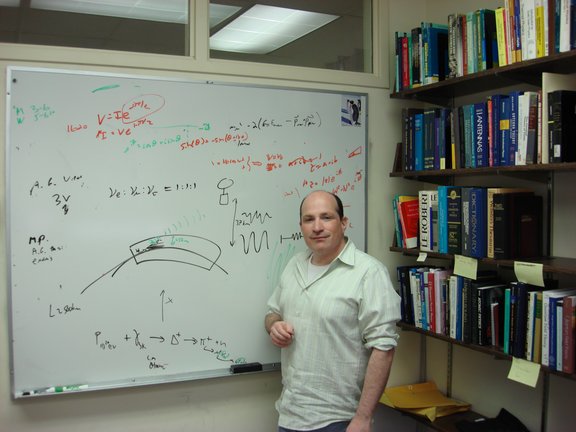

Scientific advisor David Saltzberg from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), takes care of the correct scientific background. Saltzberg works on astroparticle physics which is related to the research fields at MPIK. Currently, his group is part of the ANITA collaboration which seeks for radio wave signals created when ultrahigh-energy neutrinos from space hit the Antarctic ice shield. During a visit to California in May 2010, MPIK press officer Bernold Feuerstein stopped by at UCLA and took the chance to discuss with David Saltzberg his neutrino research and to get an interview about his contribution to the show. A transcript of the interview is given below.

__________________________

Prof. Saltzberg, how did you become the scientific advisor of TBBT – did you have any experience in working with public media before?

I had no experience before. In fact, it’s quite funny when you live in Los Angeles and you go to a party it seems like everyone works in the industry, except for the physicists. But it was really quite by chance: I have a friend, an astrophysicist I worked with in Antarctica who used to work at Caltech. And he had a friend of a friend who was involved in the show – one of the producers – and they were looking for someone to look over the script and to help them visit a graduate student apartment, to see what it would look like and they asked, you know, if I had a student who would like to do it and I said: Oh, I’ll do it, it sounds like fun. And so, that’s how it started. It started small like this with the pilot. Most pilot episodes are not picked up, and even if they are picked up many shows don’t go for more than a year, so we’re far out the tails of the distribution about that success of the show.

The scientific environment of the characters in the series is quite authentic – how important is this, in your opinion, for the success of the show?

Well, I’m sure there’s 100s of people who are scientists watching the show and they would loose 100s of viewers if the science was not correct. Of course, it’s about 14 million people viewing the show – so, you may not notice. From my point of view I worry about the science – thank you for saying so – and when there is a scientific scene like in a laboratory, for example, I will talk to the set designer about kind of things that would be in the set. The set designer has visited the labs here and taken pictures and met with people. And then individual items like you saw: anything an actor touches becomes a prop. It’s different from sets. And, for example you mentioned before about the Dewar, the vessel that contains liquid nitrogen Leslie Winkle drops the banana in. So, the props master, Scott London, asked me: how would this look like. And the miracle of the internet is, I can send him some pictures and even where to buy a Dewar and so they ordered an accurate Dewar. So, from my point of view it’s very important; though I don’t think that may be true for many else’s point of view.

So, that indicates that also the writers visit laboratories to get ideas for the setup on stage?

The writers have come and visited usually once per year; we have a few writers come by and visit. I don’t know how many ideas they get but they certainly can get a flavour for what laboratories look like. So for example after returning from here one of the writers said: OK – no lab coats! Because, as you know, physicists almost never wear lab coats. So that’s one thing they noticed and figured out on their own.

And does the cast ask you about the physics in the show or your research?

Once, there’s a scene in the 3rd season's finale where they are bouncing a laser off the moon using the retroreflectors left by Neil Amstrong and others in the Apollo Program. And they were doing the scene and it takes two and a half seconds for it to go up and come back and so they were asking me why it’s two seconds. But in general the actors are more, I think, interested in the human truth than the scientific truth.

How is your own research related to the scientific content in the show? – e. g. your neutrino research at the South Pole vs. the expedition of the characters to the North Pole looking for magnetic monopoles.

So, in fact, that was one of the rare cases, where I think there was a direct link between my own research and something on the show. I had missed a bunch of episodes that season, season 2, because I had to go to the Antarctic to launch our balloon, the ANITA balloon that I showed you. And so, I sent the writers photos and so forth and I guess they liked the idea of leaving them in the Arctic ‘cause that explains why we don’t hear from them for several months because that was at the end of the season. But to give you an idea how accurate the writers are about the show: they knew they could not send them to Antarctic because the season finale is in April. And you can’t go to the Antarctic because it’s too cold at that time, so you can’t get there. So, instead they had them go to the Arctic. But in general, the science comes from many quarters; we try to keep a variety of topics.

Do you suggest any lines or dialogues (e. g. the Leonard/Sheldon discussion in what universe we have 26 dimensions)?

In fact, things like that often come from the writers. That one in particular comes from the writers. The writers actually know a lot of science. They could actually do it, I think, without me. But what happens is: you know how scientists are, they are very nit-picky. And scientists love to watch movies and TV and find faults. So my job is to come in at the end and just tweak it up a little bit and make sure that something isn’t incorrect. But the writers keep up with science very well of themselves. And one of the writers actually spent some time as a computer programmer back in the 1980s. And they have quite a bit scientific credential.

And not only physics, as I see, if it comes to biology or history, you know, e. g. Sheldon complaining about inconsistencies at medieval festivals.

That all comes from the writers. I have no geeky background at all. Sad to say, I’m not a geek, I’m not into comic books. But this is all the real life of the writers. I don’t think they have to do a lot of research on that because it is their life. The comic books on the wall of Sheldon’s bedroom belong to one of the writers because they wanted to have the realistically important ones out there. To go back to answer one of your previous questions about the actors asking about the science I should point out that they do an enormous amount of research so they can understand, you know, what the emotional truth is behind it. In the process of doing that Jim Parsons once found out we had a mistake. We had something written as electrical dipoles instead of electric dipoles and I had missed it since it’s quite a small difference. And so, he sent an e-mail, I think, a request asking if it’s correct or incorrect and he was right – it was incorrect.

Concerning your work at UCLA: did your lectures become more popular due to your work for TBBT?

No, I don’t think so. Maybe they stay at home and watch TV.

And what about your colleagues – do they comment on the show?

Well, every week when there is a taping I can bring a physicist with. So, often I bring a graduate student or sometimes some from the faculty. So, by now most people have come through and seen the show being taped. And it’s very impressive when you see it. Really, to put a show like that on, of about 22 minutes, requires over 100 people. And they’re all running around being very professional doing their job. You can nope but being impressed when you see this operation go on as I surely was.

In general I get a lot of very positive feedback. I had positive feedback from the public outreach people of the American Physical Society. Occasionally, I get to a party and someone will grumble a little bit about the show. So, I always ask them which episode they saw. And they always say they haven’t seen an episode. It’s amazing that if you hear some grumble it’s often by people that have not seen the show.

And did maybe somebody find an error on the whiteboards and told you about?

Well, once I had an error on the whiteboard and I got an e-mail from a professor I know at California State University, Dominguez Hills, who pointed out that I had the wrong baryon in that decay; it was something he worked on. And so, he sent me an e-mail and we fixed it and a few weeks later we put it up correctly. I’ve also had an e-mail from a Caltech student about a symbol he had never seen before. But I had the original copy of what was on the whiteboard and it turned out, that he didn’t have a high-resolution TV set. But not too many mistakes have been found, but people are free to look. Of course I live in terrible fear of people finding mistakes as I know how physicists are – they love to find a mistake.

You mentioned the public outreach of APS for instance. There was a survey in Germany showing that young people become less interested in science and see more risks than benefits in it. I do not know about the situation in the USA - but could a show like TBBT help the portrayal of science?

Well, I don’t know for sure but I can say that publicity must be a good thing, I mean, because if these weren’t likable characters people wouldn’t watch. Now, its comedy, so the characters are going to be most likely flawed in some way because well-adjusted normal people are boring and not funny. So, you have to expect if that this going to be a comedy about physicists they will maybe not the most perfect representation you would like but ultimately the characters must be liked by the people and from what I hear they really are. People love these characters and that can only help the portrayal of science. But what people are thinking in their heads I really can’t know. But I do have this blog which you know about. And I’m hoping that people will sit with their laptop – like a lot of people watch TV with their laptop – and they hear a scientific term like dark matter or graphene they can just google it and learn something since there’s so little science covered in the news media these days. This way, you know, just getting those words out there may go: oh, that’s pretty interesting. Or when they took the trip to the LHC it’s another way of getting that word out there that it even exists.

Actually I got some positive feedback from the blog. But still it’s nowhere near the 14 million viewers of the TV show. That reminds me about what I said about the science in the show: Since all the comic books and geeky stuff comes from the writers, I should also point out that even if you take away the science of the show it’s still a very smart show. References in Latin to logical dilemmas, for example. There’re people out there who go to rate the grade level of TV shows. And usually bemoan the fact that it’s quite low. But the vocabulary and the ideas in this show even without the science – and this all comes from the writers – is already university level.

You mentioned the growing popularity of the show with 14 million viewers – could that weaken its science content?

So, there’s about 14 million US viewers in the first two nights. This doesn’t include Canada, Europe and South America where the show is very popular. Who knows how many people are really watching it? Regarding the scientific content I have no idea. I get the scripts as they come. And some episodes will be more science-oriented than others. Sometimes the whole story in my opinion seems to hinge on the scientific aspects such as when Sheldon was working on graphene. Other times I’m depressed to find a scientific topic to blog about. So, it’s quite a range.

And as a final question: would you like to appear on screen in the show?

Actually, I already have. Together with a graudate student in theory, actually working on one of the problems Sheldon is working on about n=8 supergravity. So, that was fun. But I think you have to be a Nobel Prize winner to get a line like George Smoot.

__________________________

Weblinks

<link http: www.cbs.com primetime big_bang_theory _top external-link-new-window external link in new>"The Big Bang Theory" on CBS.com

<link http: thebigblogtheory.wordpress.com _blank external-link-new-window external link in new>"The Big Blog Theory" - David Saltzberg's Blog about the Physics behind the show

<link http: www.pa.ucla.edu directory david-saltzberg _blank external-link-new-window external link in new>Website of David Saltzberg at UCLA

<link http: www.phys.hawaii.edu _blank external-link-new-window external link in new>Ultrahigh-energy neutrino experiment ANITA